As 2023 drew to an end, we at Project DEFY held our annual Closing Circles from 21st to 24th December 2023. Over the years, our year-end Closing Circles have become our quintessential way to place our entire year’s journey into a “complete circle” as we embark on the next one.

As an organization, if we had to pick one key learning that we would want to carry in the coming year, it would be the capacity to listen and not just hear. And this is what we did across these four days, we heard keenly with intent. Not only the team members, and learners but even our organizational partners, advisors and our well wishers were kind enough to participate as they lent their time, voice and insights.

Our first day was dedicated to our organizational partners, advisors and our extended community of well wishers whom we warmly address as “Friends of DEFY”.

Though our trusted advisors have always “steadied our ship”, this was one of the few occasions when they got to interact with the entire team to understand their viewpoints and journey at Project DEFY. Through the day the team members got a chance to align themselves with the vision of our advisors.

During the course of this session the advisors shared their feedback on the importance of exhibiting clarity and seamless execution of goals. Apart from this the team received critical feedback regarding the need of consistently communicating our impact with internal and external stakeholders.

On the same day, a point of appreciation from our session with our partners stood around how each stakeholder inspired each other through good and bad days. At the end of the session, there was a general consensus on mutual trust and accountability being the two important factors that would drive our future success.

Lastly, in our session with Friends of DEFY, we got an opportunity to share our future plans with them while also answering their questions pertaining to our vision. Towards the end we collectively brainstormed over areas of possible collaboration for future endeavors.

Our Learners, Nook Fellows and the communities lie at the heart of our movement. On day 2 of the Closing Circle, the team listened to stories of and from learners about their journeys within and outside the Nook. Apart from this, some of the Nook Fellows shared their experience of what it meant to be part of the Nook movement while also sharing critical feedback. Particularly, the team learned about what it means to establish community-centric models in different contexts.

On the same day, our various learners got the chance to personally share their stories, experiences and journeys. Many learners recounted their tales of resilience, triumphing over biases, and making choices that mirror their unique paths.

As we concluded the day, the team realized the importance of having more nuanced conversations about the various communities where our Nooks function. The second such insight from the day was the need to increase knowledge sharing among various nook ecosystems.

On the 3rd day, the team collectively took the space to introspect on the dynamics of our functioning as members of an organization. We wanted people to share their perception of the workplace from the viewpoint of inclusivity, a place where everyone felt heard, secure, and where everyone’s concerns were met. In the conversations and activities, different people voiced how they felt in several interactions. A key takeaway was the need to initiate a space for further exploration of unmet expectations.

Another key insight as a follow-up to the discussions revolved around nurturing a space where people of all genders and beliefs felt a sense of respect and dignity. To achieve this, it was decided that a series of conversations would follow with the intention to create safe spaces in the workplace environment.

Before ending the day, a final session was held where team members came together to celebrate, both, their wins and the failures they encountered over the course of the year.

The fourth and the final day of our closing circle began with the team collectively introspecting over the key observations from the first three days.

Few of the positive observations revolved around the team’s ability to bring up tough conversations and receive critical feedback. The absolute essential requirement of creating a culture where people feel free to express their opinions. As a caveat, it was also mentioned that we should not just stop at the point of self reflection and criticism, but rather identify and exhibit required affirmative action.

The next part of the final day was designated on collectively imagining a possible new identity for Project DEFY. To achieve this, all team members reflected on where we are at the moment, where we imagine to reach and what changes need to be brought in to move towards that future reality.

The team members carefully laid down the present processes that need improvement and also those which suffice our current vision but can be leveraged to build our future identity.

The concluding session of the closing circle was regarding the trade-off between passion and efficiency, at the level of an organization. The team members while being divided in groups were involved in a decision making process to evaluate a potential collaboration opportunity that Project DEFY is offered

This session allowed the team at large to reflect on some of the parameters that one has to consider while making such a choice. Some of the parameters that team members highlighted included, alignment of values and mission, understanding of the domain area and taking cognizance of one’s own capacity, both from a human and financial perspective.

Nestled in the lush embrace of nature, Assam, a state from the north-eastern part of India, boasts of a rich and vibrant biodiversity. However its landscape and social fabric is threatened by the annual occurrence of violent floods, ravaging the lives of many. The torrential rains during the monsoon, the volatile nature of the Brahmaputra river owing to excessive siltation over the years and its bank erosion, the opening of dams from the neighbouring Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh contributes to the brutal floods in the state, leaving many low lying areas inundated and waterlogged for several months. This has crippled many communities, further compounding their poverty.

DISPECS (Disaster Prepared Community Spaces), in its quest to build resilience for the most vulnerable against the wrath of natural disasters and the climate crisis, has selected the state of Assam to pilot their intervention. Therefore, the team embarked on a three week expedition in the months of July and August to understand the nature of the annual occurrence of the floods and the impact on its landscape and people. The team also met and engaged with several grassroots organisations within the state who DISPECS could potentially partner with to deploy the project within vulnerable communities who annually battle the forces of the floods. The team met with several communities from Morigaon, Majuli and Nalbari districts who bear the heaviest brunt of the floods. Several focus group discussions were conducted to explore the complex challenges and resilience factors to the recurring disaster and the dire need for sustainable solutions.

While fatalities may no longer serve as a pressing concern today, the unprecedented floods bring forth catastrophic consequences that impact myriad aspects of people’s lives. Because floods are such a frequent occurrence, communities have informal early warning systems in place, leading them to evacuate and set up camp in the highways and embankments during the period of inundation. With little to no government assistance, makeshift shelters using tin roofs of their houses become their refuge for months. With hand pumps submerged and food supply being cut off, access to basic necessities like nutritious food and clean water becomes a pressing dilemma. This leads to rationing of food by reducing their consumption to once a day and boiling the contaminated flood water for drinking purposes. The contaminated water is also used for other daily uses like bathing, washing of hands, clothes and utensils. Open defecation on the murky waters becomes the need of the hour as latrines are submerged. This leads to a host of diseases and health issues like flu, diarrhoea, cholera and rashes. Mobility is restricted in these trying times with boats being the sole mode of transportation. These boats are used to travel far and wide to hospitals for addressing their health concerns.

Being a traditionally agrarian community, the annual occurrence of floods has proven to be a bane for paddy cultivation, leaving local communities in precarity to make a living and earn scraps through wage labour and migration to metropolitan cities. With the floods jeopardising agricultural production, local farmers learnt to adapt to it by harvesting the Ahu paddy (autumn rice) by May, wherein it is traditionally harvested much later by the month of July. Similarly, there is an increase in the production of boro paddy (summer rice) which is sown in November and harvested by May. However, the erratic patterns of rainfall have prolonged the period of flooding with floods arriving as early as May. This has left people helpless, upending their lives and livelihoods.

Despite floods being a cyclical issue, the measures taken by the government to address it have remained largely insufficient. The solutions deployed are makeshift, akin to applying band aid to a wound. While infrastructural efforts like building of embankments, usage of geo bags and porcupines for preventing river bank erosion, and building raised latrines and tubewells, are notable, it is still not enough to address the gravity of the problem. These initiatives firstly, are not universally implemented throughout the state and secondly, they fall short in terms of their efficacy in providing a long term solution. Due to the inadequacy of preparedness strategies, there is an urgent demand for relief with the most vulnerable being entirely dependent on it. However, even relief is subpar and miniscule, with many communities located in remote areas not receiving it at all.

While the local communities have developed their own resilience over time, the resilience, while notable, functions at a bare minimum level of basic and meagre survival. Resilience must cater to building self-sufficiency and agency and this resilience should transcend basic survival where communities are able to withstand, and adapt in the adversity of floods. Therefore, a multifaceted and sustainable approach is the need of the hour where the affected communities first must possess the power and the capacity to become the first responders to the disasters they habitually experience.

DISPECS takes a unique approach to disaster preparedness where preparedness exceeds basic training and addresses multiple areas of breakdown of a disaster. Here, communities embrace disaster preparedness and response as a fundamental aspect of their behaviour by integrating into their daily routine and habits. This is done by introducing incentives that possess economic, cultural and/or social value for the community, during the peacetime (period of no disaster) which encourage the adoption of the behaviour and thus making it sustainable. Through these practices, communities acquire the skills, knowledge and capacity that aid them in responding to natural calamities.

Rife with stories of loss, sorrows, hope, and resilience, this expedition has been a deeply eye opening and enriching experience. Humbled, the DISPECS team looks forward to piloting the intervention in Assam, working together with the most vulnerable communities, to build lasting resilience to the perilous floods.

Author – Kareena Bordoloi

Edited by – Aagam Shah

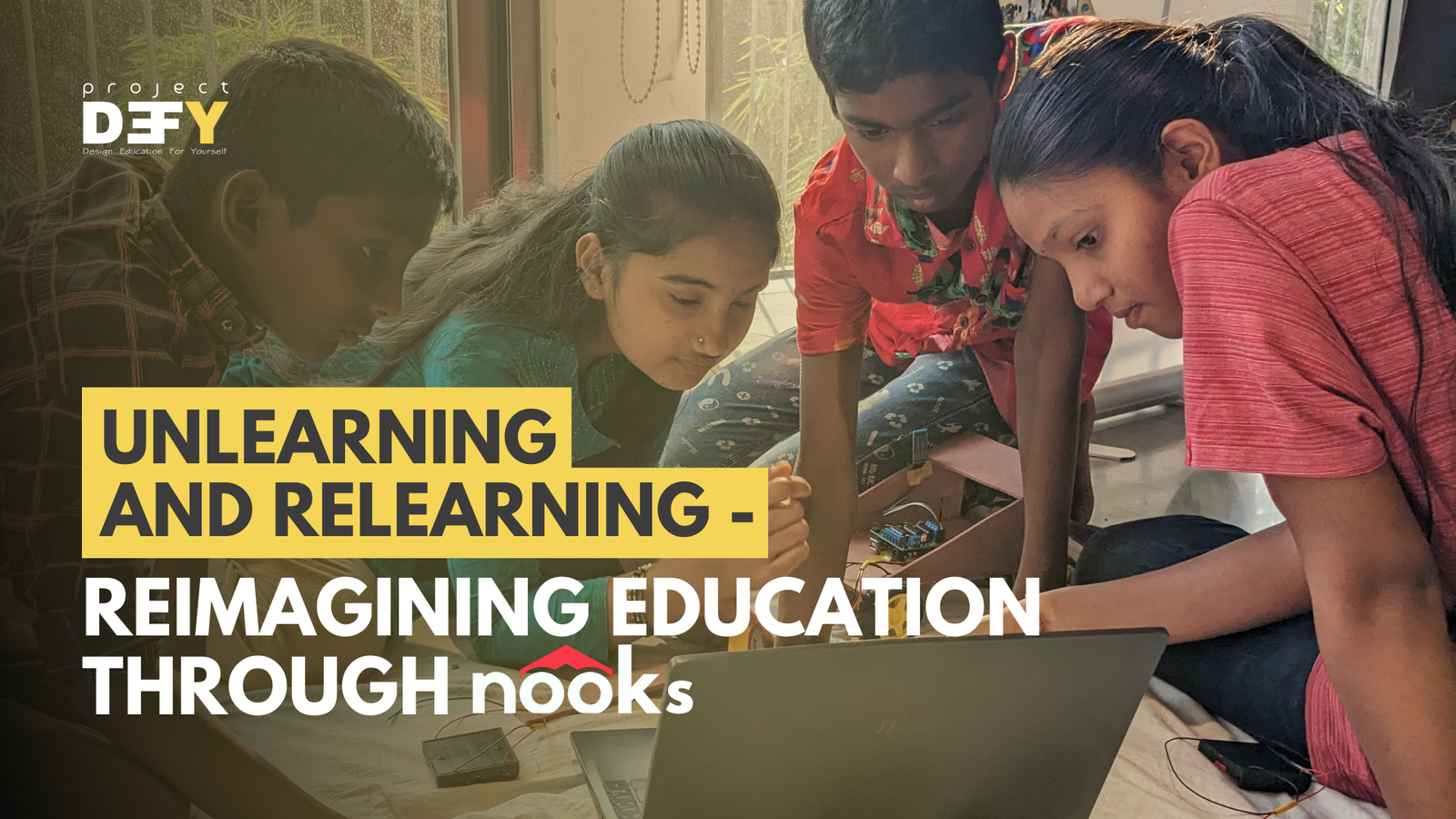

The educational landscape in itself is a vast terrain and necessitates contextual variation in our understanding of ‘what works’ to ‘fix’ education. While there is recognition of an educational crisis, in much of the ‘Global South’, conversations around solutions typically invoke images of all children having equal access to school and receiving grade-appropriate instruction. Beyond broadening access, the pursuit of ‘quality education’ includes comprehension of curriculum, which then serves as a base for progression in schools and achieving desired outcomes of education, with preparedness for the workforce receiving priority.

The linkage between schooling and employment has become so dominant that it has taken the form of what French Sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu, famously termed ‘doxa’ or “unchallenged, taken-for granted assumptions” (Gaventa, 2003) that are prevalent in society. To clarify, we do not disagree that education is a powerful equalizer or that one of the pathways of education is employment. The concern, rather, is an ‘unchallenged’ understanding of the outcomes of a ‘good’ education and the dominance of a singular truth – i.e. that educational systems are only efficient when they ultimately produce employable individuals.

Challenging doxa is no easy task. It requires a fundamental shift in understanding the plurality of educational pathways and outcomes that have existed long before institutionalized education. Alternatives do exist. However, the dominance of Montessoris, Sudburys, and Summerhills within alternate education has created a perception that seeking these pathways is accessible to a privileged few, predominantly located in affluent nations. To date, examples of alternate education in developing nations are scarce. But it is precisely where more imagination and experimentation is needed to challenge the growing pace of ecological breakdown, democratic backsliding and fragmentation of society.

Six years ago, Project DEFY, an India-based non-profit, began showing that alternate visions of education can flourish in under-resourced environments and create a form of learning that responds to many of these challenges by re-centring local and contextual knowledge. Through alternate learning spaces called ‘Nooks’[1], individuals of all age groups, genders, and socio-economic backgrounds, work together to build a community of learners that traverse a journey of collective learning and social consciousness. At a Nook, a learner is free to choose their area of interest and explore it deeply using resources ranging from the internet to technology, equipment, and knowledge of people around them. In societies where barriers to learning emerge from one’s birthplace and limit the ‘capacity to aspire’ towards futures that are unfamiliar, the Nook serves as a powerful enabler to expand and challenge these predefined trajectories. Exposure to diverse areas of learning have led learners to identify their own goals – many set up businesses to enhance livelihoods, some engaged in learning that helped solve community challenges, and others discovered their passion for a skill-set that they never knew existed before.

Natasha, a 21-year-old learner from the Nook in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, began her learning journey with carpentry, an area that is considered “a man’s job, and not meant for females” in her community. She went on to explore other areas and made shoes from locally sourced materials, created healthy smoothie recipes and shot a documentary on teenage pregnancies. In a conversation with DEFY, she explained why she worked on this documentary. “During Covid-19 lockdowns, many teenagers were sitting idle and there were a large number of teenage pregnancies. My teammate and I thought we should create a documentary to raise awareness and consulted the community members first, who thought this was a great idea. We interviewed several people including mothers who had become pregnant. They shared the challenges they faced at home and in the community. They told me that the negative perception really affected their mental health, some fell into depression, and no one was there for them. We found that some parents did not want to support their children because they felt humiliated. Our documentary wanted to show these challenges and was meant for teenagers, but also parents so that they can understand how to support their children in such situations.” Natasha mentioned that she picked up videography, how to speak confidently in front of the camera, and use editing software for the first time during this process. She aspires to refine her filmmaking skills further and take this on professionally in the future.

Often, NGO interventions and programs aimed at ‘solving’ the education crisis take on a deficit view of communities and assume the role of saviors. Natasha’s own discovery of her passion is an exemplary illustration of how being an enabler and providing access to resources, space and an unrestricted learning environment builds agency rather than an imbalanced equation of dependency. Moreover, her journey resonates with our understanding of what transforming education looks like – of learning being much larger than individual achievement, or a quest for degrees that lead to employment. Tackling problems of tomorrow require individuals to engage in educational experiences that emphasize social consciousness and are rooted in the contextual challenges communities face. We are currently on a journey to take this vision to more parts of the world.

[1] There are currently 31 Nooks running across India, Bangladesh, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Rwanda.

References

Gaventa, J. (2003). Power after Lukes: An Overview of Theories of Power since Lukes and Their Application to Development. Brighton: Participation Group, Institute of Development Studies.

[1]https://www.powercube.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/power_after_lukes.pdf/

Author : Anoushka Gupta

As I celebrated my 32nd birthday, I completed almost 8 years of harping about our mis-conceptualisation of education. A large part of the last two decades has been hijacked by an educational agenda which only gleans at the surface of a deep rooted problem. The broken record that we are not skilling our children, and that they are not ready for the industry, is a rather painful tune that I try my best to ignore. But every now and then, it permeates and gives me sleepless nights. The problem, really, isn’t that we are not skilling our children. The problem is that that is all we are doing at schools, and it is all we aspire for.

The Intertwining of Economy, Education and Development

My understanding is that while this tune was not entirely uncommon in the late 90s and early 2000s, the Aspiring Minds National Employability Report really sealed the deal in 2010[1]. It said that 80% of Indian Engineers were not hireable. This shocked the system. It was a strong criticism against the education system, and it was loud. In the decade that followed, we started seeing new words like 21st century skills, future-ready education and so on. And we started looking for ways in which our education system could churn out better employees.

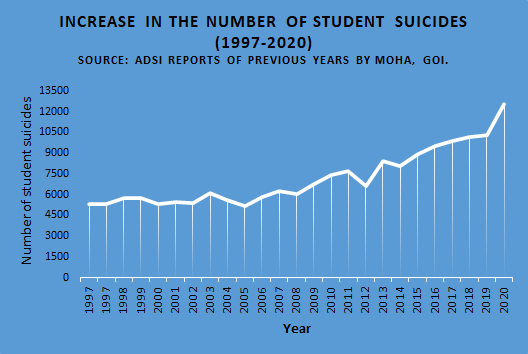

This is not surprising. Any country or society that measures its development based on economic progress alone is predisposed to see education as a means for economic development as well, and when that education cannot provide the skills required to get a job then it must is a great failure of the economic machine. Mind you, in the same breath we have also found massive levels of depression and increasing suicides among school children (see Figure 1 below), and yet these have not raised eyebrows in the same way.

Source: ‘Academic Distress’ and Student Suicides in India: A Crisis That Needs to be Acknowledged (thewire.in)

Source: ‘Academic Distress’ and Student Suicides in India: A Crisis That Needs to be Acknowledged (thewire.in)

This goes to show in a capitalist society, the “well-educated” struggle to prioritize human wellbeing and welfare over capital gain.

Here’s the catch. Wellbeing is an important factor, not just for the social fabric of people, but also for the economic aspirations of a nation. One may pick any aspiring country, and it is easy to see the correlation between the well-being experienced by people and true economic progress. Certainly, there are countries with incredible wealth and yet marking extremely low on the social scale. Wealthy nations where freedom is limited and several challenges exist, seemingly countering the theory of such correlation. And yet they are not exceptions, but instead further evidence to the truth of the theory. While such nations are wealthy, in the absence of a strong social fabric, this wealth is concentrated in the hands of very few. In the absence of social growth, one can still make economic progress, but in a severely skewed manner creating environmental collapse, military-industrial complexes and extreme wealth divide [2].

In summary, we believe skills are important, because that makes people hirable, and if they are hireable then we make economic progress. Yet, we do not make true economic progress when we ignore wellbeing and focus only on skills, making that the ultimate educational outcome.

The Training of Ignorance

The problem with Education is not skills.

The problem with Education is, well, Education.

We have a self-propagating education system which ensures that its values are passed onto the next generation of parents, teachers, bureaucrats, researchers and politicians. Most mainstream education formats openly accept that they are preparing children for the future workforce. These systems ingrain in us that life is a strugglesome competition, and that in order to succeed we must learn to defeat our friends and colleagues, sometimes simultaneously reflecting and reinforcing hierarchies that exist in society. The lives of children are turned into comparative metrics that are usually entirely made up ways of assessing learning, unrelated to even our most basic understanding of the human brain and biology. [3]

As we work our way through schooling and then university, we increasingly internalize that success is all about ourselves. That a great job, a high income and a wealthy lifestyle, which our neighbors can be jealous of, are the best indicators of success. And indeed they are in a capitalist framework. We are increasingly inclined to believe that the suffering of others is not our concern (and maybe their own fault), and our role in others’ lives is not much more than offering charity once a year. That our wealth insulates us from global problems, and we deserve this since we worked really hard for it, and it is not our place or responsibility to ask questions or make things better for the rest of the planet. After all, we are but small cogs in a large machine.

An incompetent education system thus creates an ignorant human adult. Disempowered and self-centered, he is nothing more than a machine part in the economic system and a consumer with never ending wants.

And is he happy? He tries to remind himself that he is, everyday. And when it becomes difficult, happiness may come in the form of a new perfume or new shoes or an expensive car. He waits for weekends to find happiness in short holidays and evening soirees, or a once-in-five-years vacation that he secretly hopes would never end. For there is no joy in the everyday, and he must contrast the boredom and listlessness with a once-a-while instagrammable smile.

We were wrong

We made a mistake. We did not see the monster.

We have been blind to the failing of the education system as a whole. We have not questioned it and challenged its existence. And the true malice of education systems around the world is in its rather clever tactic of passing off the blame to students and terming them as , and .

But, it is wrong. And we must first acknowledge that. We cannot continue living in denial and constantly finding new ways to justify the system, thinking that it requires only a few minor fixes and iterations. The education systems we call mainstream today are perfect – perfectly evil; designed to disempower. We have to find imagination and courage to dream new education models, ones that truly empower and enhance the most beautiful aspects of humanity. Our learning spaces must be spaces where trust and love is experienced daily. Where learners slowly build confidence in themselves, and are not scared to ask the hard questions. Where what they do is an outcome of who they are and who they wish to be, and not the other way around.

This is hard because we are all already infected. We must escape our programming and be prepared to be surprised. We have to go back to the whiteboard, and ask the questions – what do we want? What will make this world a better place? What will make us happy? What will ensure that we thrive as a society? And we cannot be distracted again by the lurking thought of economic progress. This will come anyway, and in a much better way than we would find by making it our sole goal.

I believe there must be some truth to what Gary Vaynerchuk said about money –

“People are chasing cash, not happiness. When you chase money, you’re going to lose. You’re just going to. Even if you get the money, you’re not going to be happy.”

We must stop chasing money and defining our success entirely in terms of economic progress. Let’s start with education.

References

[2]https://www.oecd.org/social/economy-of-well-being-brussels-july-2019.htm

[3] https://blog.minervaproject.com/four-reasons-exams-are-ineffective-in-measuring-learning

Author : Abhijit Sinha

Edit : Anoushka Gupta

The last few weeks have been a wonderful reminder of the difference between being a tourist and being a traveller. Moving across the ancient and sacred land of Egypt, I have been a traveller. Travelling is not really in seeing and doing, but instead in being, and as such a rare opportunity that requires the right people to come together at the right time. To truly be a traveller, one must be ready in body and in mind, willing to open up to the land, its people and its experiences; and then the land and its people must open their hearts to you. It’s a strange chemical reaction, a spiritual drama that allows for an unpredictable story. The Ecoversities Gathering and the Yatra (travel) afterwards has been such a story.

The Ecoversities Gathering brings together each year some of the most daring and imaginative educators from around the world. Educators who are attempting to redefine the very word I have just used to refer to us; trying with all our might, and with a smile, to imagine a new society and ecology that has a chance to survive the neoliberal onslaught. For the six days of the gathering we live in such a society of shared values of liberation and love. It is not inundated in meaningless speeches and dress codes and business cards, but rather engages through a sharing of stories, practices and emotions. Life is slow, and the learning is fast. There is not enough time, and yet there is always more time. The 2022 Gathering hosted by Sara, Samy, Yousef and the HajMoulein Farm Community in the deserts of Siwa has been an experience that is very hard to talk about or write about. It is a lived experience, and I can only do a poor job of using words to express them. I apologize in advance.

The Gathering received educators and learners (both embodied in all of us) from all over Asia, Africa, the Americas and parts of Europe. Many languages were spoken, many translations happened. The principle at heart is inclusion, and not simply as a checkbox that corporations have to use, but as an intent that we share together. The responsibility of the gathering was shared by all the gatherers, and this includes the cooking, doing dishes, cleaning toilets, organising the space, taking care of the animals and making the environment that we wish to share with ourselves and others. Volunteers were called to sign up for tasks each morning and many times, I saw more hands than the requirement. How amazing this is! A counterculture of the economic world where we usually dislike doing things for others or even for common good. This little world in the desert was different, and did not carry the burdens of the transactional world.

Anyone is welcome to tell a story or host a session. Want to be buried in the sand? Want to discuss feminism? Want to understand your anger? Sure! All kinds of explorations were possible and happened. We heard war stories, love stories, stories of death, of birth and rebirth of a new world emerging slowly under the sands of time. There’s hugs if you need them. Or a Namaste if you do not like touch. A pat on your back if you have always wanted one. There’s honour and respect, not for the position you hold or the work you do, but for the sacredness of the humanity that resides within you. There is love for your presence and appreciation for your thoughts. There is space for all, the young, the old, the child, and however you imagine your outer and inner beings to be.

After a soulful and emotional six days of the gathering, and the tremendous beauty that Siwa has to offer through its hot springs, salt lakes, old temples and structures, we started off the Learning Journey or Yatra. Aptly named El-Rehla (the Journey), 22 of us started traversing the country. We of course had big plans of things to see and do, and projects to visit. But we were also committed to ensure space and time for ourselves to slowly connect with each other (and sometimes disconnect with our usual realities back home). In Marsa Matrouh, our first stop, we shared stories in pairs walking along the Ageeba Beach that eases into the Mediterranean Sea with bright turquoise waters. We moved on then to the busy Corniche of Alexandria staying in a very old and charming Greek apartment overlooking the shores. The sunset at the El-Max village is something out of a dream. The colossal library is hard to miss. The city is really fast, but we were on a different timezone altogether. After Alexandria we stopped in Cairo, visiting Ci-las, a wonderful project started by my newfound brother and friend Karim. It is heartening to see the role of liberal studies in liberation and the on-going struggle as a human society. The final part of the Yatra took us to Fayoum where we stayed in the astonishing Tunis Village (again, a place made of dreams). A swim in the lake in the middle of the desert was the perfect ending to the Yatra. The fact that the lake cannot be seen unless you really get close was the summary message of our journey in Egypt. In order to get a glimpse of the country, you must really get close. And is it not true for every place, and every person we meet?

I have told you the places. It is impossible to recount or describe the conversations. I don’t think I even remember everything. Memory, in the conventional sense, I think, was not the most important aspect of this journey. We must look at memory differently, maybe in the way the sands look at time – in infiniteness and abundance. The conversations, the visits and the interactions, you may not remember them, but they certainly change you. They affect you in the smallest and yet the biggest ways, in part and as a whole. I return physically tired, but mentally recharged, with a myriad of connections not defined by transactional partnerships but instead bound in the fine and strong strings of love.

If you are reading this, and are feeling that you missed out something, you really don’t have to worry. Yatras happen many times in a year, and many local gatherings too. May not be the same place, or the same people, but I can assure you that it will be magic. Gift yourself a learning journey the next time you see one, and keep an eye on the Indian Multiversities Alliance and the Ecoversities Alliance pages

If a child is unable to sleep,then their parents often use the threat “sleep at once or masterji (teacher) will come”. This shows how ingrained education, schooling, teaching, etc are in the minds of the parents. From the day a child is born, the parents start thinking about their future and where and what they will study. Going to a traditional school is ofcourse the first thought.It is indeed ironic because children have to be literally dragged out of their beds to school. In fact many parents take loans, some face financial distress in funding school/college education of their children. They think that the child will learn something worthwhile and lead a happy-successful life, but after 14-15 years of education they find the child has not developed any real-world life skills. I spent 14-15 years in utter boredom by attending various classes of uninteresting subjects through school and colleges. The period of my life where the neurons of mind had to be developed, I had to develop the muscles of my hand by taking notes in those boring classes. A couple of days ago I was talking to a 7th standard student and in his words “We are totally fed up with our teachers in the school. They never let us have any fun and make us write notes all day long. We go to school to just write and write and write. On top of that, if we don’t write the same thing in the exam, word by word, we will fail the exam.”

The existing education system has propagated the values of memory and recalling systems of the human brain the most. The other requirements like thinking and social abilities, creativity, curiosity etc are almost non-existent. The very things which will help the children

to survive and thrive in the world are not developed. The classroom model of education was developed in the 19th century when the industrial revolution started. The factories needed workers and clerks who would just follow orders and do their repetitive tasks without any

questions. The 21st century is no longer the same. World has changed a lot in these 200 years. But our education system remains the same.

We now live in an interconnected world. Information is available to everyone at a click of a button. Hence, we require a new education system in this changed world. Following are the requirements of the new system which should be fulfilled.

- Exclusive focus to be given to individuals.

- The learners should have the choice to decide what, how and how much they want to learn.

- Empathy with fellow human beings, living beings and the environment should be at core of it.

- The learning process should be engaging, experiential and fun filled.

- There should be hands-on activities for almost all the things to be learnt.

- The learning and its usefulness in the real world should be made clear to the learners.

There can be various ways of fulfilling the above requirements for a new education system. One can go to an alternative education model. Others could get home schooled. Some may want to restructure the existing schools. We just need to make sure the learners learn to think, learn by themselves, ask questions and find answers and connect with the community. The problem posed by the current education system is widespread across the world. Innumerable number of people have identified these problems and attempted to solve them. Some noteworthy solutions one can find are Shikshantar, Auroville, Shantiniketan, Project DEFY, Summerhill School and so on. These organisations are working to provide a proper

learning environment to the people from marginalised communities. Even though we set a new system we must be careful enough to not make it rigid. There should be enough flexibility to accommodate the changes which come from time to time. Bringing an overhaul in the education system has to start with overhauling of our minds. We have to unlearn first and then move on to learn again.

About The author

Nishant Kumar is a computer engineer by degree and a maker enthusiast and community builder by heart. He can be seen learning and helping others learn new things anytime. He has been facilitating learning sessions for tech and design topics. If not working, he can be seen enjoying music or roaming in nature.

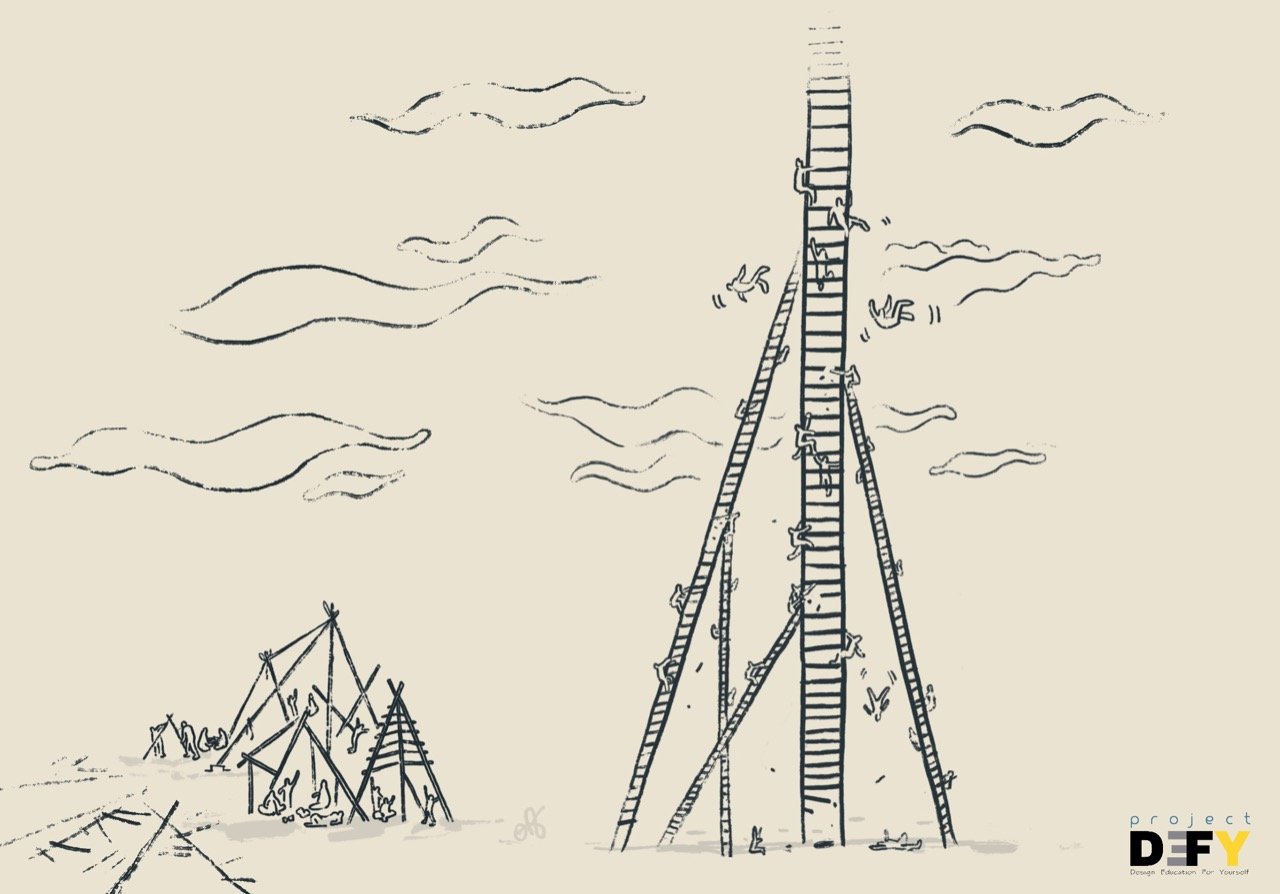

It is no surprise that we’re witnessing one of the biggest turnovers of what defines human value and its methods or perception of ‘educating’ in history, for all that stood for schooling (information holding and dissemination) is smoothly being taken over by memory chips and the internet. Existing school and college systems are largely at stake of losing all relevance, as collaborative capacities, run for initiatives or instant thought becomes far more valuable than degrees. And as our digital seconds tick, we are closer than ever to realise the futility of the mindless competition and egocentric ideas of ‘success’ our colonised minds have so long adhered to. To such an extent, that we feel completely lost and miserable without a given goal or a checkpoint, probably a hangover of the slavery under the British rule.

Not that we’ve completely gotten out of it, or that the numbness of an enslaved mind has left us, but we surely have started questioning our ideas of ‘success’ and ‘necessities’.

Experimentations and re-evaluations in education, at least in India, have been ages old. But for relatability and a counter colonial narrative, we can go back to 1920’s; when a resourceful and acknowledged figure (in the world of literature and otherwise) tired with the factory model of classroom schooling, decided to have classes under open skies and banyan trees, with complete interdisciplinary courses which continue till date. And no wonder it brought out few of the most diverse and acknowledged minds in the world of cinema to the world of economics. Rabindranath Tagore, thus, can be taken as one of the foremost examples of those in India who pioneered experiential learning, with symbiosis and self-realisation as core values, countering the absurd idea of British schooling (which were no more than prisons training ‘well behaved’ clerical slaves).

There were several others including Mahatma Gandhi (idea of swaraj), Sri Aurobindo (Auroville) who have tried to, and to certain extent have, successfully established spaces and ideas of exploratory and experimental schooling, and a human society where growth and thought are driving factors. It is a mind-boggling phenomenon, however, to see ‘globalisation’ cause such an impact, that even after seventy years, people are still being sold mono-cultured and linear ideas of success, where it is an imaginary ladder to climb, while ensuring that others are left behind. And the only way to climb that ladder is with an IIT certificate, without which one might as well imagine a deadbeat existence. If we care to reimagine the world, we must look beyond the usual faces of success, the famous CEOs and Billionaires and Investment Bankers, and find new ones that have succeeded in life differently.

Jail University, Udaipur

The inmates here, at the Central Jail of Udaipur, try to explore activities which are close to their hearts, discovering a sense of freedom during their time in prison. This includes a variety of things, from permaculture to theatre to painting, through a wonderful program called Jail University. One of the faculty-inmates for the program, began his journey at the jail six years ago, when according to him he, along with his father and grandfather, was falsely accused of a crime and sent into prison. Following an intensely difficult phase and getting a lifelong sentence, on the verge of giving up, he found painting to be his companion and guide through the program. From intricate drawings for drawing books to painting murals on walls, he found his calling. Took him nine months to master his craft, and some amount of resilient faith to start passing it on to twenty other inmates, who plan to continue it professionally when they get out. This program aims at shifting the societal outlook of imprisonment, punishment and crime to a more inclusive process of lifelong learning and a journey of finding one’s true calling.

HIAL (Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh) and SECMOL

The name of Sonam Wangchulk rings a familiar bell after the popularity of how the success rate of matriculation results in Ladakh’s villages took a sharp increase within a decade of introducing SECMOL (Students Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh). A program introduced after he worked together with the government and villagers into making the school curriculum more relatable and inclusive of local culture. For those still struggling to cope up, he introduced this alternate school, HIAL, which takes learning to its core, making it fun, hands-on and experimental. From agriculture to eco-friendly buildings to starting campus radio or newspapers, this place could be a live example of what a community of solution builders, rejected by the generic schooling systems could accomplish, given an inclusive space. For more specific examples, we could consider two of the learners who had earlier failed their matriculations repeatedly four to five times. One went to become a top journalist and later education minister, while another a renowned filmmaker with multiple awards. Thus, the examples of those rejected by conventional institutions blooming at the chance of necessary and adequate spaces are endless.

JP Nagar Nook, Bangalore

Another such story which can’t go unmentioned would be that of Niah, and her ongoing journey of exploration and self-directed learning, from JP Nagar nook. For those unfamiliar with nooks, these are physical self-learning spaces within communities, where learners of all ages and genders can come together, explore and learn through projects of their choice. Niah, left her school after 12th and got married early, to a household where she wasn’t allowed to do much outside household work. She discovered the nook while coming to drop off her sons, only to find out she equally belonged to this space. A space without any teacher, a strict code of conduct or exam, one where you could simply be. Laptops and the internet opened a whole new world for her; she started learning English and the possibility of exposure immensely boosted her confidence. She is still figuring out how to use her newly acquired skills but is glad to have found a voice and not be constricted in the household anymore.

There are endless examples of such journeys, where young and creative minds, rejected by social structures of schooling and education, have flourished the moment they have found enough space to ‘grow’ and to ‘be’. From Albert Einstein to Thomas Edison to Leonardo Da Vinci, we could keep looking at known figures who made a positive shift in the course of humanity but were seriously rejected by their schools and teachers.

That brings us to a very basic question – Can a student or person ever be a ‘failure’? Or is it the school which fails when it labels its student as ‘failure’?

In fact, what kind of a society is evolved, if it’s idea of nurturing is based on exclusion? It is like choosing the plant which is already in full growth and bloom, and providing it with more food and water, taking credit for its growth. No wonder the gap between the richest and poorest, economically, and culturally, has only been ever increasing. No wonder linear ideas of growth and success are devouring all possibilities of diverse thought and solutions, with every bit of human essence left in them. We’ve already lost touch with most of our cultural roots and the mind-boggling diversity they held, their crafts and knowledge, mostly vilified by schooling systems.

Since we are at the verge of a major crisis which is ecological, economical, educational, societal and political, it is a good time to think about taking a small pause; rethink our ideas of success, growth and happiness and ask ourselves, ‘if everything around us appears to be ‘garbage’ or ‘failures’, who or what has really ‘failed’ ?

Then, we can hold up these existing stories, which took the courage of going beyond the norms, giving curiosity, imagination and the human ‘being’ a chance; and use them to inspire enough such stories and spaces, that they fill up this existing void of neglect and rampant rejection.

For what use is a school of, if it doesn’t know how to include and create enough space, for each to grow?

About the author

Archisman is an explorer and storyteller with special interest in the impact of visual design and architecture in everyday life. He likes painting walls, listening to teatime stories and working with organisations or communities aiming for a more conscious, symbiotic future.

“There can be no contentment for any of us when there are children, millions of children, who do not receive an education that provides them with dignity and honor and allows them to live their lives to the full.”

– Nelson Mandela

As a society, we all consider education as a tool of empowerment, growth and development for the communities and nation as a whole. School, colleges and universities as an agent of education are seen as the ‘great equalizer’ of income, wealth and historical inequalities or injustice between different communities, poor and rich, men and women. Education has become the ultimate solution to all of the problems in our societies. Through the right based approach, education has become the priority of many governments, civil societies and NGOs. The present education system promises so many things; reducing poverty, gender equality, social or inter-generational mobilities, skilled workers etc. It also promises to solve various problems like unequal access to different institutions, climate change, etc.

For centuries School Education has been granted the status of utmost good, the most benevolent task for humanity – to educate its children to continue the world. It is undeniable that children do grow to become the future of society, of humanity and of the planet. However, what are the parameters that we are setting for ourselves and for this education? What lens are we willing to use to measure the worthiness of the placement of the modern education system at the pinnacle of human good?

The word ‘education’ rings different bells for different age groups of people. And if one cares to ask those who are getting educated , one thing that would be clear is – it’s definitely not an enjoyable process. Maybe that’s one of the factors that have contributed to a generation of frustration and compulsiveness, feeding on mass produced opinions and judgement, losing everything that is human. What was to be an exploration leading to evolution, growth and mindful symbiosis has merely become a painful training process to yield lifeless consumers who can be put under formulae, assessed and controlled, thus becoming forever dependent on an external entity.

So as an organisation working towards building conscious spaces for self sustainable community learning, where learning is fun and empathy is more than a moral science topic, we consider it an immediate responsibility to uncover the face of existing education system and call out the sins it has committed on the human essence, one by one.