As I celebrated my 32nd birthday, I completed almost 8 years of harping about our mis-conceptualisation of education. A large part of the last two decades has been hijacked by an educational agenda which only gleans at the surface of a deep rooted problem. The broken record that we are not skilling our children, and that they are not ready for the industry, is a rather painful tune that I try my best to ignore. But every now and then, it permeates and gives me sleepless nights. The problem, really, isn’t that we are not skilling our children. The problem is that that is all we are doing at schools, and it is all we aspire for.

The Intertwining of Economy, Education and Development

My understanding is that while this tune was not entirely uncommon in the late 90s and early 2000s, the Aspiring Minds National Employability Report really sealed the deal in 2010[1]. It said that 80% of Indian Engineers were not hireable. This shocked the system. It was a strong criticism against the education system, and it was loud. In the decade that followed, we started seeing new words like 21st century skills, future-ready education and so on. And we started looking for ways in which our education system could churn out better employees.

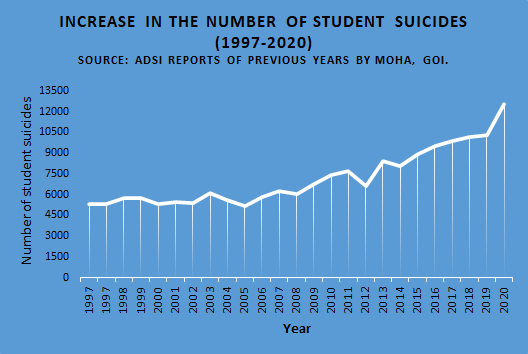

This is not surprising. Any country or society that measures its development based on economic progress alone is predisposed to see education as a means for economic development as well, and when that education cannot provide the skills required to get a job then it must is a great failure of the economic machine. Mind you, in the same breath we have also found massive levels of depression and increasing suicides among school children (see Figure 1 below), and yet these have not raised eyebrows in the same way.

Source: ‘Academic Distress’ and Student Suicides in India: A Crisis That Needs to be Acknowledged (thewire.in)

Source: ‘Academic Distress’ and Student Suicides in India: A Crisis That Needs to be Acknowledged (thewire.in)

This goes to show in a capitalist society, the “well-educated” struggle to prioritize human wellbeing and welfare over capital gain.

Here’s the catch. Wellbeing is an important factor, not just for the social fabric of people, but also for the economic aspirations of a nation. One may pick any aspiring country, and it is easy to see the correlation between the well-being experienced by people and true economic progress. Certainly, there are countries with incredible wealth and yet marking extremely low on the social scale. Wealthy nations where freedom is limited and several challenges exist, seemingly countering the theory of such correlation. And yet they are not exceptions, but instead further evidence to the truth of the theory. While such nations are wealthy, in the absence of a strong social fabric, this wealth is concentrated in the hands of very few. In the absence of social growth, one can still make economic progress, but in a severely skewed manner creating environmental collapse, military-industrial complexes and extreme wealth divide [2].

In summary, we believe skills are important, because that makes people hirable, and if they are hireable then we make economic progress. Yet, we do not make true economic progress when we ignore wellbeing and focus only on skills, making that the ultimate educational outcome.

The Training of Ignorance

The problem with Education is not skills.

The problem with Education is, well, Education.

We have a self-propagating education system which ensures that its values are passed onto the next generation of parents, teachers, bureaucrats, researchers and politicians. Most mainstream education formats openly accept that they are preparing children for the future workforce. These systems ingrain in us that life is a strugglesome competition, and that in order to succeed we must learn to defeat our friends and colleagues, sometimes simultaneously reflecting and reinforcing hierarchies that exist in society. The lives of children are turned into comparative metrics that are usually entirely made up ways of assessing learning, unrelated to even our most basic understanding of the human brain and biology. [3]

As we work our way through schooling and then university, we increasingly internalize that success is all about ourselves. That a great job, a high income and a wealthy lifestyle, which our neighbors can be jealous of, are the best indicators of success. And indeed they are in a capitalist framework. We are increasingly inclined to believe that the suffering of others is not our concern (and maybe their own fault), and our role in others’ lives is not much more than offering charity once a year. That our wealth insulates us from global problems, and we deserve this since we worked really hard for it, and it is not our place or responsibility to ask questions or make things better for the rest of the planet. After all, we are but small cogs in a large machine.

An incompetent education system thus creates an ignorant human adult. Disempowered and self-centered, he is nothing more than a machine part in the economic system and a consumer with never ending wants.

And is he happy? He tries to remind himself that he is, everyday. And when it becomes difficult, happiness may come in the form of a new perfume or new shoes or an expensive car. He waits for weekends to find happiness in short holidays and evening soirees, or a once-in-five-years vacation that he secretly hopes would never end. For there is no joy in the everyday, and he must contrast the boredom and listlessness with a once-a-while instagrammable smile.

We were wrong

We made a mistake. We did not see the monster.

We have been blind to the failing of the education system as a whole. We have not questioned it and challenged its existence. And the true malice of education systems around the world is in its rather clever tactic of passing off the blame to students and terming them as , and .

But, it is wrong. And we must first acknowledge that. We cannot continue living in denial and constantly finding new ways to justify the system, thinking that it requires only a few minor fixes and iterations. The education systems we call mainstream today are perfect – perfectly evil; designed to disempower. We have to find imagination and courage to dream new education models, ones that truly empower and enhance the most beautiful aspects of humanity. Our learning spaces must be spaces where trust and love is experienced daily. Where learners slowly build confidence in themselves, and are not scared to ask the hard questions. Where what they do is an outcome of who they are and who they wish to be, and not the other way around.

This is hard because we are all already infected. We must escape our programming and be prepared to be surprised. We have to go back to the whiteboard, and ask the questions – what do we want? What will make this world a better place? What will make us happy? What will ensure that we thrive as a society? And we cannot be distracted again by the lurking thought of economic progress. This will come anyway, and in a much better way than we would find by making it our sole goal.

I believe there must be some truth to what Gary Vaynerchuk said about money –

“People are chasing cash, not happiness. When you chase money, you’re going to lose. You’re just going to. Even if you get the money, you’re not going to be happy.”

We must stop chasing money and defining our success entirely in terms of economic progress. Let’s start with education.

References

[2]https://www.oecd.org/social/economy-of-well-being-brussels-july-2019.htm

[3] https://blog.minervaproject.com/four-reasons-exams-are-ineffective-in-measuring-learning

Author : Abhijit Sinha

Edit : Anoushka Gupta

Nook: Whitefield

Learner Name: Monisha (Not real name)

Month & Year of Story: January 2020

13-years old Monisha attends the 7th grade at St. Joseph’s Convent School in Whitefield. Her father is a day laborer working mostly for construction projects while her mother is employed as a maid across several households in the community. Both parents are working hard every day to feed their family of four so that Monisha is often necessarily left on her own. After school, there are no spaces to go for children in the local community and no activities offered. This changed with the establishment of the Whitefield Nook.

Now, coming to the Whitefield Nook on a daily basis after school, Monisha explores a wide range of new areas and acquires many skills and new knowledge in the process: “I’ve never seen or been to a space like the Nook before which contains so many tools and materials that we all can use. I never used a computer before in my life, but after coming to the Nook I have learned how to work on a laptop and access information online to find new projects. I have improved my typing skills, knowledge of computers, how to browse the internet and learned how to make electronic projects,” the girl says.

As opposed to school which severely limits the choice of what one can learn and how to learn it, Monisha particularly enjoys the freedom of finding and working on her own projects, based on her own needs, interests, and dreams: “In school, we only study books and never apply what we learn, but in the Nook we can explore and build any kinds of projects which we are interested in. The Nook is a good place to improve our skills and it will help you to learn whatever you want,” she argues. Another aspect Monisha mentions is that in the Nook, people learn together and with each other rather than having to compete against each other for grades and recognition. “I enjoy working in a team and in the Nook I am getting that opportunity. That’s also what makes me come to the Nook every day. It’s nice to work together and have fun at the same time,” she adds.